Derailed?

Threats to state’s smaller railroads could hamper economic development efforts

By G. Chambers Williams III

The Tennessean

Across Tennessee and throughout the nation, hundreds of short-line railroads work around the clock to deliver raw materials and finished products on thousands of miles of tracks that, for the most part, were once operated by the nation’s major railroads.

For economic developers, these short lines are a key tool in their efforts to attract new industry.

“The Nashville and Eastern (Railroad) is vital to us,” said G.C. Hixson, director of the Wilson County Joint Economic and Community Development Board. “With a lot of these heavy industries that we’re trying to recruit, you’re not even in the running if you don’t have rail to offer. It’s necessary that we have the service, and that we have property available along these rail lines.”

Unlike the big Class 1 railroads, such as CSX and Norfolk Southern, these smaller lines — known as Class 3 railroads — run on short stretches of track that largely have been abandoned by the Class 1 lines because they weren’t profitable — or profitable enough to justify keeping them in their systems.

Tennessee has 18 short lines, with nearly 900 miles of track, most of them created by the state and local governments that stepped in to save routes they saw as necessary to keep industries that rely on rail shipments. In many cases, taking over those lines saved precious jobs. Some have some really big customers, such as the short line in Chattanooga that serves the new Volkswagen plant. Since these authorities took over, the state has spent more than $80 million to rehabilitate the lines that had mostly fallen into disrepair in their final years under ownership by the Class 1 railroads, said Val Kelley, managing director of the Lebanon-based Nashville and Eastern Railroad Authority. Money for the track work comes from the state’s Short Line Equity Fund, which gets its money from a 7 percent tax the state charges on diesel fuel for railroad locomotives.

That fund has now been frozen as the result of federal court lawsuits by the Class 1 railroads claiming that the tax is discriminatory, a move that now threatens to shut down the state’s entire short-line network. In mid-October, a federal judge in Nashville stopped the state from collecting the tax, and payments to the shortline railroads were suspended pending the outcome of appeals.

And this court fight could have major implications for companies across the state that rely on these rails to conduct daily business.

Recruiting industry

Two recent successes for Hixson’s department were made possible by having the Nashville and Eastern Railroad, he said.

Kenwal Steel Corp., based in Dearborn, Mich., opened a sheetmetal processing plant in the Martha community in Lebanon in 2007, and the Italy-based So.F.Ter U.S., a plastics company, now has a plant under construction next to Kenwal that is scheduled to open early next year. Together, they will account for several hundred jobs.

“Having short-line rail service gives us an opportunity that other communities don’t have to attract those kinds of heavy industries that traditionally pay more than others,” Hixson said. “Kenwal Steel is one of our higher-paying employers.”

Kenwal’s plant supplies rolls of cut sheet steel primarily to automotive seat manufacturers throughout the South and Midwest. The sheet metal comes in on rail cars — about 140 a month, said plant manager Phillip W. Shaub. It ends up in Ford, General Motors and Chrysler vehicles.

“Rail was a key part of our decision to locate here,” Shaub said. “We keep 30,000 tons of raw material on the floor here at all times, and almost all of it comes in by rail. One rail car can bring in four times as much steel as a single truck. Without that service, we would be at a competitive disadvantage.”

Industries also like working with the short lines more than with the larger railroads because they feel they get better service, Shaub said.

“We’ve had other locations on the Class 1 lines, but we wanted the kind of customer service you get from a short line,” he said. “We’ve worked well with the Nashville and Eastern. I can pick up the phone and get the president of the company on the line. I could never get the president of CSX to take my call — I probably couldn’t even get their dispatcher.” The Nashville and Eastern also runs trainloads of crushed stone from Gordonsville to Nashville for the Rogers Group, and brings in hoppers full of sand from amine in Monterey for asphalt and concrete producer LoJac in Lebanon and Hermitage.

“The railroad is extremely important to us,” said Rogers Group CEO Jerry Geraghty. “After river barge, rail is the most-efficient form of transportation. It’s much more efficient on a train than a truck, and in this market, short-line railroads are a critical part of the transportation network. We do some transport on CSX, but the short line here is very responsive and easy to deal with. Customer service is one of their strengths.”

Nashville and Eastern/ Nashville and Western President Bill Drunsic helped found the two lines in 1986 as the state Department of Transportation was setting up the network of rail authorities that took over the routes abandoned by the Class 1 railroads.

“We were already operating a couple of railroads in the western part of the state, and this came up and was a larger operation,” Dunsic said. “We took the opportunity, and we helped negotiate the purchase price of the line from Nashville to Monterey. We’ve grown substantially over the years, and we serve a number of key industries in the area.”

Kenwal Steel is the biggest customer of the Nashville and Eastern, followed by the Rogers Group, Drunsic said. On the Nashville and Western, the top customer is Trinity Marine, whose plant along the Cumberland River just south of Ashland City makes river barges. The raw steel for the barges comes in on the trains.

Customer service

While Drunsic’s railroad company is responsible for routine maintenance of the lines, major projects such as bridges, new spurs and upgrades — like the improvements necessary to run the higher-speed Music City Star passenger trains — have until now been paid for by the state’s Short Line Equity Fund.

“We’re going to be in a real bind if we don’t have that money anymore,” said Kelley, whose authority handles major improvements on the Nashville and Eastern route. “We’re also looking at extending our line to Oliver Springs, where it would connect to the Norfolk Southern.”

Drunsic said that extension is a priority of his company, as well. “Our long-term goal is to connect the end of our line all the way to Knoxville so there would be a mid-Tennessee route from Memphis to Knoxville,” he said. “That area between Monterey and Knoxville was deliberately broken up in the bankruptcy of the Tennessee Central to eliminate competition, back in the time before trucks became so dominant.” Besides freight traffic and the Music City Star, the Nashville and Eastern Railroad also hosts about two-dozen passenger rail excursions annually, operated by the Tennessee Central Railroad Museum near downtown Nashville.

“Some go as far as Watertown, some to Cookeville, and a couple times in spring and fall they do the entire line,” he said.

For now, the short-line authorities are waiting for word as to when or whether their funding will continue. The Nashville and Eastern Railroad Authority has a $255,000 payment due in January on a $2.5 million loan it took out to pay for improvements that allowed the Music City Star to run on its tracks.

It has a $405,000 payment due in June on the $7.5 million loan it received to rehabilitate the line from Cookeville to the LoJac sand mine in Monterey.

“We have no idea what’s going to happen,” Kelley said. “Without the state’s help, we can’t make these payments. That’s where the money comes from, and we have no other source of funds.”

The short lines are looking to the legislature to come up with a permanent solution to the funding crisis, he said.

These two side-bars accompanied it:

A Day on the Short Line is full of Stops

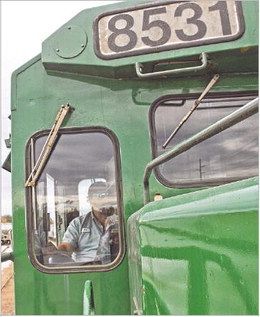

Engineer Bill Woodruff opens the throttle and the giant General Electric locomotive begins moving the Nashville and Eastern Railroad train out of the rail yard at the end of Stanley Street near downtown Nashville.

Today, the GE Dash-8 diesel is pulling about a dozen cars, most of them loaded with plastic pellets along the route east toward Hermitage.

At the end of the train is an open car stacked with gypsum wallboard, destined for Valley Interior Products, just a few hundred yards away. That car came in earlier in the day from the junction with the CSX Railroad near 100 Oaks Mall.

Conductor David Sarnes hops off the engine, opens a gate, and then Woodruff backs the train into Valley Interior’s lot, disconnects the car and leaves it there to be unloaded.

On this day, the train will make the trip up the line’s Old Hickory Branch, a 14-mile run to the rail yard next to the former Du Pont plant. There, the carloads of plastic will be dropped off, some for the Fiberweb plant that uses part of the old Du Pont property to make plastic wraps and textiles. Others will be left there for a trucking company, Hoffman Transportation, which offloads the pellets into long, green hopper trailers that take the product to plants that manufacture a variety of plastic goods.

On the way back, there are other stops. More plastic beads are dropped off at FlexSol Packaging on Visco Drive, which makes plastic bags. Some empty cars are picked up from Mid-South Wire Co., whose plant is on the same spur line, and the train heads on back toward downtown.

It’s all in a day’s work for the Nashville and Eastern, a small railroad operation known as a “short line,” whose trains run over the 110 miles of track between Nashville and Monerey on the old Tennessee Central Railroad line.

“My day is filled with backing up, pulling forward, and backing up again,” Woodruff said.

The first 30 miles of the line, between Nashville and Lebanon, also serves the Music City Star commuter service.

— G. Chambers Williams III

TENNESSEE SHORT LINE RAILROADS

There are 18 short-line railroads in Tennessee, most of them operated by governmental rail authorities and leased to private operators. Nearly 900 miles of track are under the control of the short-line operators, and they haul millions of tons of commodities annually, handing the shipments over to the Class 1 railroads such as CSX and Norfolk Southern. Middle Tennessee short lines include: » Nashville and Eastern Railroad Authority, upon whose tracks run trains of the Music City Star commuter line and the privately held Nashville and Eastern Railroad, a freight carrier. It runs 110 miles from Nashville to Monterey. Key customers: Coca-Cola, Kenwal Steel, LoJac Materials, Mid-South Wire, Georgia Pacific, Dow Chemical. » Cheatham County Railroad Authority, operated by the Nashville and Western Railroad Corp., 16.7 miles between Nashville and Ashland City. Key customers include Ashland Chemical, Jefferson Smurfit and U.S. Tobacco.

Another key short line operating in Middle Tennessee is the R.J. Corman Railroad, which runs from Cumberland City through Clarksville to Guthrie, Ky., and will serve the Hankook Tire plant in Clarksville.

This photo accompanied the first sidebar:

Bill sure takes good care of that engine!